Imagine the scene. It’s Easter, the last Cadbury Crème Egg has gone missing overnight. Your child is looking sadly up to you, his guru, the beacon of truth in his life. ‘What happened daddy?’

There are three easy answers.

- Tell the truth… ‘I ate it last night, sorry.’

- Lie…‘The dog ate it’

- Lie a lot… ‘Your egg was the Crème Egg of God and it’s gone back to live in heaven, although it might appear to you in a vision tomorrow.’

There’s a lot of talk about lying right now. Many of the world’s political leaders, like kids in a Cadbury Creme Egg shop, have discovered a world where they can make things up, change their story, deny the absolutely undeniable and somehow get away with it. In some cases they become more popular as a result too.

It won’t last…probably, but until someone comes up with an effective strategy to deal with it (like presenting themselves as an actual, believable opposition) don’t hold your breath.

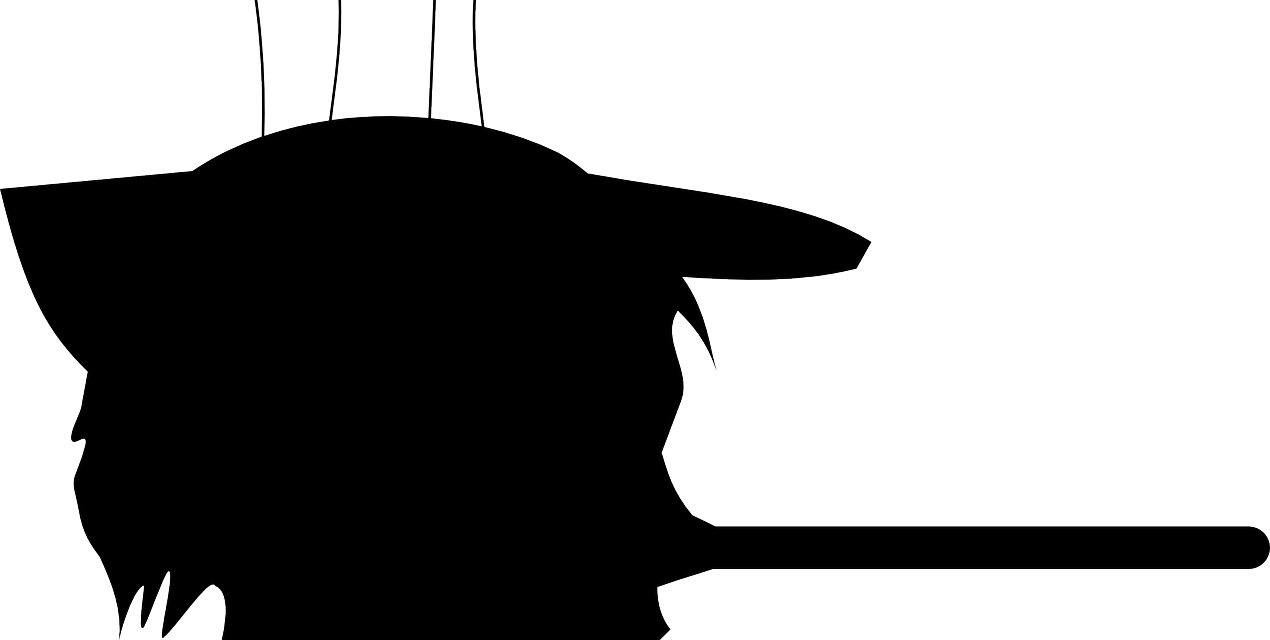

What’s interesting here is that there are many ways to not tell the truth and some are much more effective than others. Those like Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and Donald Trump, just go all-out shameless. Make something up, go back on what you said and then be adamant that you never said it at all and replace the original lie with yet another one.

And the public seem to love them for it because (and I can only suppose here) that self-same public, made up of ordinary human beings either does exactly the same in their own lives and so, finally sees a politician that reflects their views, or aspires to be as big a liar as they are and get away with it too.

This kind of pantomime lying is a long way from the politician’s traditional tactic of either refusing to give the actual answer to a question and just talking around it (also known as the Labour Party) or coming out with a patronising, meaningless, banal platitude (Michael Gove’s approach), which the public rightly despises.

It’s part of human nature to play with the truth. We all do it. Sometimes it’s a reflex – we’ve been caught doing something wrong or not done what we’d promised and when challenged, instead of just admitting it, we make something up to try and wriggle out. Not a lie, we tell ourselves, just a spirited self-defence.

And then there’s the exaggeration. Wanting to impress people we invent or embellish events in our past to make us seem more interesting. Again, we know it’s wrong, but, hey…everyone does it because there might be a snog/fumble/movement up the macho hierarchy or a promotion at the end of it.

A few years back I worked for a big company in a small town. The owner – a man in the same small town – had a reputation for having a temper and most of the employees, including the directors were terrified of upsetting him. So, whenever anything went wrong the first thing they did was look around to see who was to blame. This process generally involved the directors ambushing a few bemused staff on that age-old premise of ‘Can I just borrow you for a minute?’ before giving said staff a sharp talking-to, little or no chance to check what had happened, find out the truth or be able to give an answer that might ensure it never happened again. Usually, those staff did what we all do when ambushed and went into survival mode, making-up their own half-baked reasons why it wasn’t their fault.

Having been on the receiving end a couple of times, I decided to take a different approach. As soon as a problem was discovered – any problem…in any department – I stood up immediately and accepted full responsibility…for everything…all the time. Somehow, I argued, at some point, as a senior manager, something I had either done or not done must have led in some small way, via the ripple-effect to this problem.

It worked too. The directors were happy because they were clearly not responsible. The other managers and staff were relieved to be spared the spanking. And instead of wasting half a day dodging blame we could get on and work out what to do to make sure it didn’t happen again.

I never got sacked or told off and always had a friendly and professional relationship with the supposedly ogre-ish owner, who seemed like a very smart pussycat to me.

It didn’t stop me exaggerating my abilities every now and then or embellishing the odd story when I was hoping to impress people, but it did change my approach to work. And it ties in with what a lot of business gurus are promoting these days – the idea that failure is part of the process of becoming successful and we should embrace it, not be afraid. ‘Fail fast’ is the suitably macho term we can get behind without losing credibility.

And the one place this new way of working ought to start is at the top of politics. Imagine if a politician, asked a tricky question by a constituent or journalist, simply replied with the truth?

Imagine also if they had the guts to accept they’d got it wrong, it was their fault, they made an honest error and here was the revised plan to put things right…quickly. The current Covid-19 crisis is a really good example of this. Most of our politicians are caught between not-causing-panic by appearing to be not in control and being honest with the public that things are changing so quickly as we get more data each week that the strategy is bound to evolve. If Matt Hancock, the Health Secretary openly admitted that the logistics of delivering so much PPE to so many places on such a frequent basis was beyond the systems Government had in place, then rather than look like an idiot, he would actually look like a man needing help. And maybe, the likes of Amazon, DHL or the Post Office, who solve these issues every single day would realise that this was their time to stand up and be heroes.

So, how do we go about creating this new culture? Where do we start? How about with the journalists? They are the people who could and should be helping to nurture this culture because, in the perpetual chase for a soundbite, too much political journalism is about coaxing someone into a statement that can then become the headline for the rest of the day’s news.

The challenge for news journalists is they are required to be Jacks and Jills of very many trades. It’s impossible (or unlikely, at least) for one person to be both a skilled interviewer and an expert on economics, healthcare, foreign policy, transport and home affairs and so, having asked their pre-planned questions (presumably thought-up during a briefing with others who should have expertise), when their interviewee gives a slippery answer it’s the follow-up questions where things go wrong. And to be fair, most of the politicians aren’t experts either. The Ministers for Health, foreign affairs and education or any of the major offices of state almost never have a serious, credible background in those subjects, so it’s not surprising that they can’t debate the detail.

How many times have you watched an interviewer repeating the same question again and again because the politician isn’t answering it, when a smarter, informed inquiry that develops the conversation and allows the interviewee to accept that the policy being discussed is fluid would have actually moved the conversation along and maybe got closer to a solution.

Just supposing we created a culture where instead of the relationship between journalists who weren’t experts and politicians in a similar position being adversarial, it became more like a conversation that allowed each of them to develop their thinking in the company of the watching millions.

Key to that is creating a culture where the truth is valued and people are happy to take responsibility for when things don’t go to plan, because, sometimes the plan is evolving.

Going back to the top of this story, imagine the rumpus if God had created the animals on the Earth in the same, measured way instead of employing the Michael Gove approach to managing policy. The elephant would have had enough discussion around its specification to have ended up with a proper, conventional nose, whereas what happened was probably this.

Mrs God, “Have you seen the hosepipe Jehovah, I want to water the grass.”

Mr G, “Oh, erm, no. Have you looked behind the hot tub?”

Mrs G, “No, something’s sucked the water out and blown it over Gabriel – he’s very cross. By the way, what’s that grey thing behind your back?”

Etc